Light-Writing from Las Vegas

Alan N. Shapiro

All photographs © 2017 Alan N. Shapiro

This photo-essay was published in 2017 in the book “Nevertheless: 17 Manifestos AND Digital Culture” edited by Andrea Sick, Textem Verlag, 2018.

From Dublin, Ireland I traveled on to New York City, then to southern California to meet up with my long-distance girlfriend. The America trip had begun. Moments after entering Nevada by car, we encountered Whiskey Pete’s casino. Here an important Jean Baudrillard “simulation and simulacra” conference had taken place in 1996. It was dusk as I walked alone across the parking lot, my right jeans pocket loaded down with American quarters (25 cents coins) that I needed to quickly sacrifice to the slot machine gods.

I knew that I was standing at this spot for perhaps the only time in my life. The first and the last time. “No two moments of your life are exactly alike” — the clichéd sentence from some book on Buddhist spiritual consciousness that I had read rose up in my mind. But I am a materialist. I want to win some money, right now.

Taking photos in this casino was allowed. I had struck Umberto Eco-travels-in-hyperreality semiotic gold.

The juxtaposition of blackjack tables and McDonald’s hamburgers inside Whiskey Pete’s casino was an amazing stroke of luck. Fast money and fast food. Save on dinner so you can lose at the tables.

I spoke with a security guard. I told him that I am from Germany, and that I found this living image to be an extraordinary snapshot of American culture and of what makes us Americans great, especially for those of us Americans who are Germany residents and who love the writings on America of the French writers Bernard-Henri Levy and Alexis de Tocqueville. The security guard had no idea what I was talking about. He replied in deadpan, becoming the protagonist of the story: “We have McDonald’s at all three of our properties.”

Located at the California-Nevada state line in the town of Primm, Whiskey Pete’s hotel and casino is 35 miles from downtown Las Vegas.

In November 1996, the apparently French media theorist Jean Baudrillard traveled to Nevada to headline at The Chance Event at Whiskey Pete’s Casino.

America is not a cultural desert.

“I [in this case, Chris Kraus] organized The Chance Event for my own reasons. Is there anything that happens, ever, that really matters, that is not a confluence of mutual self-interest? You are not American if you do not believe this. In 1996, I’d left New York for Los Angeles after 15 miserable years of trying to be an experimental filmmaker. I’d started writing I Love Dick, which one year later would be published as my first novel.” (from Chris Kraus, “Chance-Event” in Philosophie und Kunst. Jean Baudrillard, Merve Verlag, 2005)

Nowhere motels. Discarded oil drums in a sprawling garbage dump.

On a dark desert highway, cool wind in my hair. (Eagles (1977). Hotel California. Lyrics by Don Henley and Glenn Frey. © Asylum Records. – HC for further reference)

See the ripped-out pay phones.

Up ahead in the distance, I saw a shimmering light. (HC)

You feel the blast of heat stepping out onto the parking lot pavement under the arid sun, leaving the air-conditioned casino. Architectural shapes bounced from a limousine’s opaque window.

“DJ Spooky would travel from New York to give the “Keynote Address” in the form of an ambient trip-hop performance.” (Chris Kraus)

Mirrors on the ceiling, pink champagne on ice. And she said: We are all just prisoners here, of our own device. Some dance to remember, some dance to forget. (HC)

“We also rented ten adjoining rooms to set up Hotel California, an ambient, site-specific art show organized by Sarah Gavlak and Pam Strugar.” (Chris Kraus)

Gambling in the “hypermodern” context is neither purely an entertainment activity nor an activity pursued with the hope of making money without effort. It is both.

Gambling is a paradox. It is an entertainment activity which has as one of its key elements of attraction the possibility of making money without work. Its appeal to the player consists precisely in the tension between these two aspects. The strategy of the casino management is to immerse the player in a highly controlled semantic and semiotic environment. The player would never consent to gamble if he knew that the exchange consisted of the purchasing, for a certain sum of money, of a temporal unit of participation.

On the other hand, the player never really believes that he frequents the casino in order to make money. If he or she did, he or she would not pass through the ritual of persuading him/herself that his/her expenditure was the price of a legitimate consumer activity in which he or she had the right to periodically indulge. The paradox of gambling lies in the quantum physics complementarity between the packaging of an entertainment experience and the desperate illusion of instant monetary gain.

In casino gambling, the player is, on the one hand, aware of the objective reality of the casino situation: the house advantage, the management’s profit calculation, the laws of probability. But, on the other hand, he or she is not deterred from playing because he or she believes in an ideology of “personal exemption” and “beating the odds.” He or she rationalizes that the sequence of wagers and outcomes will move along a different level of causality than that of probability. Each player believes that he or she will be the one to evade the objective determinations and inexorable reality of profit calculation.

This “doublethink” (George Orwell, 1984) is analogous to people’s attitudes in general towards social structure and economic and cultural determinations in their lives. Although we are aware that a society with definite organizational patterns exist, we tend to detach ourselves from this awareness and to emphasize our autonomy as individuals, our decontextualized self.

Casino gambling as an embodied metaphor for our situation in hyper-modern society. The semantics of the casino environment: the management’s project of designing a total, controlled environment and selling a packaged consumer experience to the players. The semiotics of the transformation of the value of money inside the casino. Money becomes chips. The player is deprived to some extent of the awareness that he or she is playing with real money.

Four aspects of the design of the casino: the exclusion of time and outside rituals; architecture; the panoply of symbols of affluence; and the audiovisual display of winning.

Inside the casino, there is an elimination of the difference between day and night. The same activity (gambling) continues uninterrupted twenty-four hours a day. There are no clocks visible anywhere in the casino. There are no windows. There is an architectural impression of limitlessness. The casino may consist of one enormously large room, perhaps the size of a football or soccer field. You cannot see the other end of the room upon entering. Abundant mirrors create the effect of an infinite refraction. There is a minimization of columns, giving the impression of an entirely suspended ceiling.

For the gambler who stays at the adjoining hotel, the manufactured design environment is even more encompassing. Everywhere there are shops, comfort facilities and services. The gambler does not need to seek the “satisfaction” of his “needs” anywhere else. The valuation of the consumer experience of losing money is enhanced by its presence in the total design ambience where other commodities and symbols of “the good life” are on prominent display.

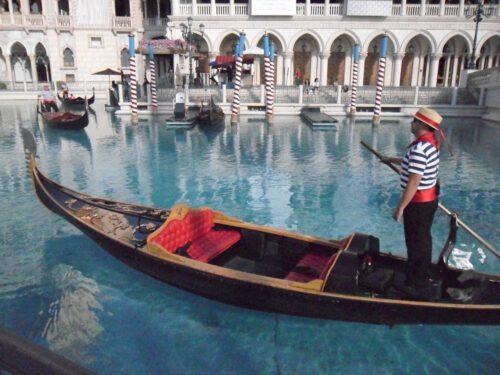

The simulacrum of “the good life” substitutes for the good life itself. The simulacrum replaces the real. The semiotics of ancient Rome replace the real historical Rome. The replica St. Mark’s Bell Tower and the replica Rialto Bridge at the Las Vegas Venetian Resort Hotel Casino replace the real Tower, Bridge, and the city of Venice. The Eiffel Tower in Las Vegas replaces the one in France and the city of Paris. Donald Trump’s Taj Mahal (Atlantic City) replaces the ivory white marble mausoleum in the Indian City of Agra.

Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. The famous Venetian bridge called the Rialto was a hub of anti-semitism in Shakespeare’s time. At today’s Las Vegas Venetian hotel-casino, there is a nice Jewish deli called The Rialto.

The simulation of Venice in Las Vegas, its cultural-imaginary presence in the former desert of the former territory of Nevada, down to the details of gondolas, canals, and bridges.

The Rialto Bridge and the Campanile of St. Mark’s Church. The Campanile (bell tower) was last restored in 1514, when it reached its present form. It was rebuilt in 1912 after its collapse on July 14th at 9:45 A.M.

Since the probability of winning in the casino is small, every surprising instance of winning is highlighted and underscored through bells, lights, jackpots, video displays, computer animation, and the cheering that one sometimes hears from another roulette or craps table. When someone wins a large jackpot at a slot machine, the event is loudly proclaimed through all sorts of media everywhere in the casino. I don’t lose. I win. I’m a winner. We’re winners.

The casino presents a certain version of populist “democracy.” You belong to this imaginary shared democracy — as long as you can afford the $15 minimum stake to place a wager at a table. You can sit there until your stack of chips runs out. Your right to be there, your simulated equality, is never questioned during the game. Regardless of your “net worth” on the outside of the casino, here you play against the same mathematical odds. I can sit down at the same table with the CEO of a company or a Wall Street stockbroker. But as soon as I am out of chips, I no longer exist. The casino is done with me. I can go to an automated teller machine in the lobby and get more instant cash from/on/with my credit card. I can retire to the casino periphery of the twenty-five cent slot machines.

In most forms of casino gambling, the player is confronted either with a machine or with a highly trained representative of the casino. He or she is almost always playing against “the house.” There is an atmosphere of subtle hostility among players, often an avoidance of social interaction. Disruption of the game’s small rituals (hand gesturing in blackjack when to “hit” or “stick”, the appropriate moment to maneuver one’s chips) is greeted with disapproval.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) is a major work of British literature that belongs to the “castaway on a desert island” tradition, in the same lineage as Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Johann David Wyss’ The Swiss Family Robinson (1812). These great works of world literature are part of the legacy and background of the TV show Lost, which itself now belongs to world literature, as upgraded for and in the contemporary age of advanced media technologies.

Treasure Island is a story about Pirate Treasure. There is a secret and mysterious treasure buried on a remote Island surrounded by ocean waters. This immense treasure was accumulated not in the most upstanding and scrupulous of ways. It was accumulated by Pirates who robbed and pillaged on the high seas.

The brown old seaman who stayed for a long while without paying at the Admiral Benbow Inn in the seaside village of Black Hill Cove tells of the treasure at Treasure Island. I remember it all so clearly. He arrived with his old sea-chest containing all of his worldly belongings, dragging it behind him on wheels. He was a rugged, eminently masculine man.

Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest –

Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!”

Drink and the devil had done for the rest –

Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!”

The old seaman who called himself Captain Billy Bones was perpetually on the lookout for a fellow seafaring man whom he described as having only one leg. This man turned out to be the amazing character Long John Silver. Bones dreaded the possible arrival of Silver. I had terrible nightmares half-consciously imagining in various horrific forms (the severed limb portion cut off at different heights of the leg) this notorious legendary creature.

Some time later a strange sailor named Black Dog shows up at the Admiral Benbow Inn. After Billy Bones arrives in the dining room for breakfast, the two former shipmates sit together and engage in a conversation that soon turns hostile. A sabre duel ensues, and Black Dog is wounded in the left shoulder. Billy Bones collapses from a stroke. He takes a fall in the parlour, and I see him “lying full length upon the floor.” The Doctor and I carry Billy upstairs and lay him out on his sick bed. I care for Billy over a period of time. He confides in me that he once sailed the seas as First Mate serving under the command of the great notorious pirate Captain Flint. The appearance and disappearance of Black Dog indicates the presence close by of Billy’s remaining crewmates who are still alive and who want to confiscate his old sea chest.

We hear the sounds of a group of rascals approaching, and my mother and I go into hiding. Seven or eight pirates, led by the blind man named Pew who had visited before and had given Billy Bones the Black Spot, descend upon the Inn in search of the chest. The pirates are not especially interested in the money, but rather in the very same object that I had removed from the chest: the oilskin bundle which they refer to as “Flint’s fist.”

I was going to sea myself; to sea in a schooner, with a piping boatswain, and pig-tailed singing seamen; to sea, bound for an unknown Island, and to seek for Buried Treasures!

Due to the genetic code he shares with other Vulcans, Mr. Spock can “withstand higher temperatures, go for longer periods of time without water, and tolerate a higher level of pain” than humans. (Whitfield and Roddenberry, The Making of Star Trek) Spock is more resistant to radiation and needs less food to nourish himself than his non-Vulcan counterparts on board the Enterprise. Physical distress, for Spock, is merely a kind of information input.

Lt. Commander Spock does not perspire. He has much greater physical strength than his human colleagues. He has more acute hearing, resulting from evolutionary accommodation to sound wave attenuation in the thin atmosphere of Vulcan. Spock has an extra inner eyelid to protect his vision against strong solar and electromagnetic rays.

By the late 1960s, NASA personnel embraced Mr. Spock as one of their own. Leonard Nimoy was invited to be guest of honor at the March 1967 National Space Club dinner, and to take an extensive tour of the Goddard Space Flight Center. The actor concluded from the warm and intense reception that he received that astronauts, aerospace industry engineers, secretaries, and shareholders alike all regarded Star Trek, and especially the character of Mr. Spock, as a dramatization of the future of their space program.

The stance of opposition to a war undertaken by America’s “military-industrial complex” (MIC), as President Eisenhower termed it in his Farewell Address to the nation on January 17, 1961, seems to be based on the assumption of the discursive viability of projecting oneself into the imaginative space of being a sort of “shadow government of truth-speakers”, empowered by democracy into the democratic position of being able to make “better” decisions for the body politic of democracy than those who hold institutional power in political economy and government. Most political discourse in the U.S., including the anti-war stance, seems to take for granted the idea that we should clarify “our politics” by imaginatively putting ourselves “in the shoes” of national strategists choosing among the policy options available.

Much of what we know about the Holocaust, World War II, and the Vietnam War comes from Hollywood films about the Holocaust, World War II, and the Vietnam War that we have seen. In his essay on Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 blockbuster Vietnam War movie Apocalypse Now, Baudrillard writes that Coppola’s masterpiece is the continuation of the Vietnam War by other means. “Nothing else in the world smells like that,” says Lt. Colonel Bill Kilgore. “I love the smell of napalm in the morning… It smells like victory.”

The high-budget extravaganza was produced the same way that America fought in Vietnam, says Jean Baudrillard of the film made by director Francis Ford Coppola. “War becomes film,” Baudrillard writes of Coppola’s spectacularly successful cinematic creation. “Film becomes war, the two united by their shared overflowing of technology.” (Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, University of Michigan Press, 1994) There is implosion or mutual contamination between ‘film becoming Virtual Reality’ and War. Think also of Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998): total immersion in the Virtual Reality of combat – an aesthetics of VR different from ‘critical distance’ – as a new kind of ‘testimonial position’ with respect to war and atrocities.

Following the tradition of early architectural critics like Ada Louise Huxtable and Jane Jacobs, it has become the mainstream consensus view among New Yorkers “in the know” that the Pan Am Building (now called the MetLife Building) is a hideous slab structure that brought congestion to the area, blocked the magnificent Park Avenue vista, and shrouded the iconic masterpiece of the New York Central Building. For me, on the contrary, the imposing midtown edifice exists in a different dimension. In a partially hidden parallel universe, the Pan Am Building is a “monster” architecture in the positive, ironic sense of issuing a challenge to the urban space of New York City – a radical illusion beyond the officially lamented (lack of) aesthetic sensibility of its builders. The structure is dense, but leaves space for movement. There is an elaborately engineered system of human circulation and interconnections between places of business and the train terminal. The many high-speed elevators and complex of escalators are complemented by the intricate passageways and tunnels leading to rail and subway service. Poised above the commuter stations, the construction choreographs an open expanse or austere transitory ambience to the ticketing promenade surrounding the majestic analog clock. Home on its upper floors to innumerable tiny windowless offices housing foreign currency changers and language translation agencies, the parallel universe Pan Am Building is symbolic of a secret affirmative cultural exchange of America with the rest of the world.

The edifice’s octagonal shape and east-west perpendicularity to the buildings lining the north-south arranged streets institute a singular communication to peers. The structure shrewdly divides Park Avenue into north and south segments rendered invisible on the ground to each other. On the skyscraper’s flat roof, the heliport of NY Airways offers a speedy transfer to LaGuardia, JFK, or Newark airports – a thrill ride to be discontinued in 1977 after a fatal helicopter crash. In Escape From New York (1982), Snake Pliskin makes a perilous landing of his one-man stealth plane onto the flat top of one of the World Trade Center Twin Towers.